In its lower case, “über das sprechen” points to the double meaning of the words. On the one hand, the exhibition deals with language, addresses the theme of capitalized speech in its various dimensions, in its questions about what is said with speech, what is triggered mentally, or what is concealed with the help of language and its media. The other variant of the exhibition title is understood as an invitation to speak about “that”, which as a demonstrative pronoun is a reference to something that only acquires meaning from the context or the knowledge of the speaker. The audience of the Schwerin exhibition embarks on this search for context when they engage with the theme of speaking in various media.

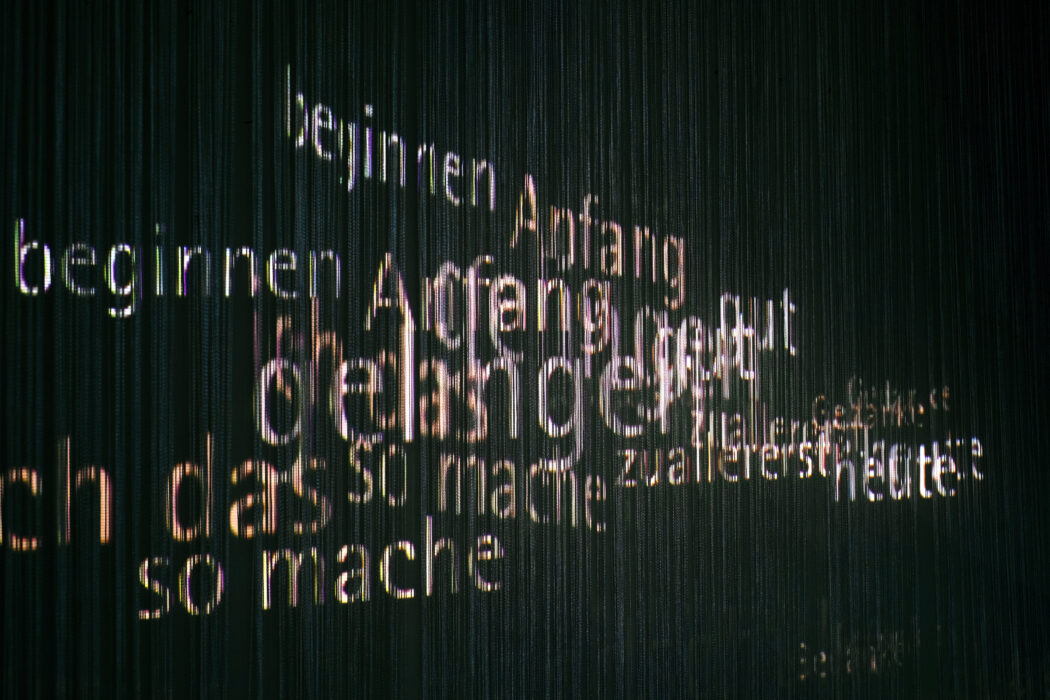

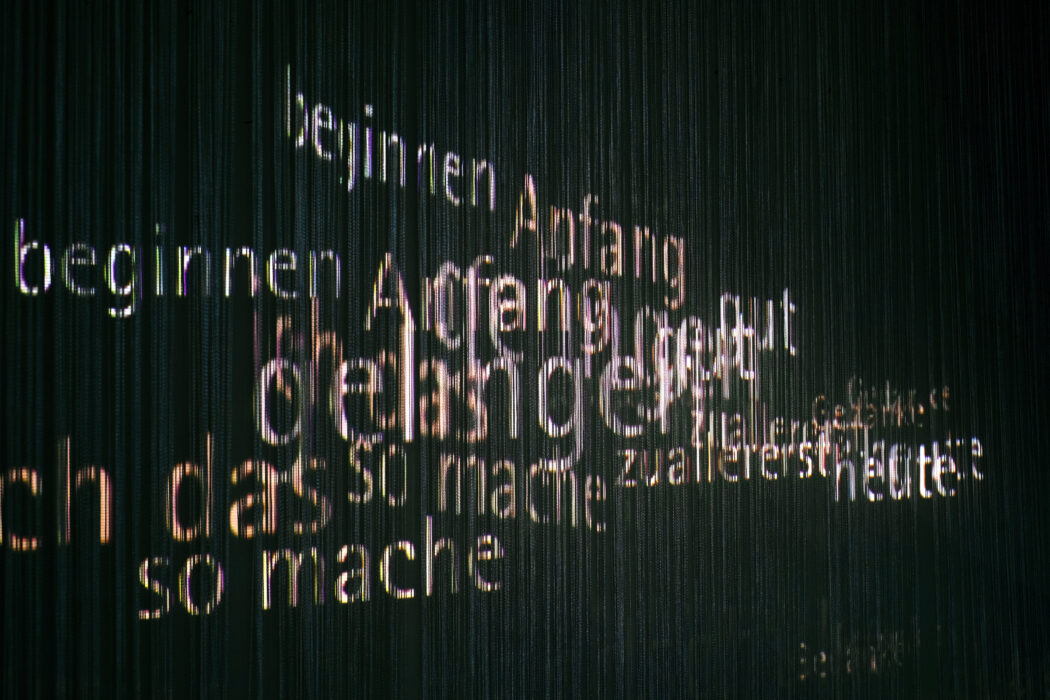

The room-filling video installation FIVE MINUTES is reduced to written language alone, supported by a sound composition by Stefan Hoffmeister. Words are projected via three beamers onto curtains of thread, surrounding the viewers in the center of the installation on all sides. The word sequences simply begin with “I,” “you,” and “we” on one projection surface each. At the beginning, the sentences seem to make sense, but the viewer is soon overwhelmed when trying to read all the words. Words break through the syntax and rather result in rhythmic patterns, underlined by the metallic technoid sounds of the electronic music. Depending on individual attention, the contexts change, become ambiguous – such as “bleeding” or “sanctuary” – and suggest various possible contexts for the fragmentary narratives. The title of the media installation is its exact playing time of 5 minutes. It is that familiar five minutes that is demanded in everyday speech as a small favor, time that seems to be left over: “Give me five minutes and I’ll explain.” But they are also the vague five minutes of procrastination: “Five more minutes…” and the speaker has done a job, cooked dinner, or possibly slept in. Those five minutes in which the addressee regains full attention.

The series of paper works of the SPEECH GRIDS shows forms that at first appear abstract as ornaments or technical patterns. The perforated grids have real models. Speech grids are protective covers for intercom systems. They help to enter or to give emergency signals in the elevator, in the train to talk to the driver. The metal covers protect the speaker, but allow sound to be transmitted through the holes. What they have in common is that they use simple technology to mediate between interior and exterior space via a secured threshold. They are idiosyncratic media of transfer, of transition, sometimes industrially produced, sometimes amateurishly drilled by hand. The series shows a typology from different countries, such as Italy or France. The perforated grids produce almost two-dimensional patterns, yet Sachsenmaier shows that they lead into a third dimension behind, which, however, like the counterpart, remains in the remains in the dark.

In the video installation GO TO THE LIMIT, the audience is confronted with cinematic portraits of people who continually and intently list nationals, such as Mauritanians, Israelis, Italians, and many more. The sitters are male or female, of different ages and, judging by their language, belong to different nations themselves. The monitors are mounted on desks set on edge, reinforcing the impression that the enumeration is being documented like a bureaucratic act. The viewer is initially confronted with the question of the categories according to which the named nations were selected by the speakers. Their once thoughtful, then cheerful or also very certain intonation lets fictitious criteria arise in thoughts. The task that Andreas Sachsenmaier gave the portrayed people was simply, to name the names of members of different nations.

The designated objects are also not visible in the video installation MOJO 2. Short sentences call for action. They are advertising slogans formulated in the imperative or as suggestive questions. The sentences rotate around a horizontal axis like a gambling machine, slow down and stop. Which message each visitor goes home with is decided by lucky chance. The short film Parkour leads through the Aue Pavilion of documenta 12, but the exhibition has not yet opened. Throughout the film, no art is visible, only the wrapped works already stored in the pavilion during construction and the elaborate exhibition architecture of the greenhouses, with which curator Peter Bürgel wanted to create a transparent atmosphere. Sachsenmaier films the shrouded exhibition from a moving lifting platform, opening up a new perspective on the art and its spaces. Titles of works are superimposed so that film viewers with some knowledge can guess what lies behind the transparencies and the massive amounts of paper. In this exhibition tour, the art becomes visible only through the titles, now completely nominalized. Sachsenmaier closes the exhibition with this work, language has taken the place of sensual perception.

Andreas Sachsenmaier shows worlds of language to which the viewer to which the viewer has no direct access, similar to the way in which the non-representable is described in the theater via the “Mauerschau”, by the narrator looking over a wall. The video installations and paper works reveal structures and systems of communication. The view of the envelopes and the concealment sharpens the attention for the respective media and their modes of operation. The concentration on language makes us think about understanding, about that “that” around which speech revolves. (Dr. Christina K. May)

In its lower case, “über das sprechen” points to the double meaning of the words. On the one hand, the exhibition deals with language, addresses the theme of capitalized speech in its various dimensions, in its questions about what is said with speech, what is triggered mentally, or what is concealed with the help of language and its media. The other variant of the exhibition title is understood as an invitation to speak about “that”, which as a demonstrative pronoun is a reference to something that only acquires meaning from the context or the knowledge of the speaker. The audience of the Schwerin exhibition embarks on this search for context when they engage with the theme of speaking in various media.

The room-filling video installation FIVE MINUTES is reduced to written language alone, supported by a sound composition by Stefan Hoffmeister. Words are projected via three beamers onto curtains of thread, surrounding the viewers in the center of the installation on all sides. The word sequences simply begin with “I,” “you,” and “we” on one projection surface each. At the beginning, the sentences seem to make sense, but the viewer is soon overwhelmed when trying to read all the words. Words break through the syntax and rather result in rhythmic patterns, underlined by the metallic technoid sounds of the electronic music. Depending on individual attention, the contexts change, become ambiguous – such as “bleeding” or “sanctuary” – and suggest various possible contexts for the fragmentary narratives. The title of the media installation is its exact playing time of 5 minutes. It is that familiar five minutes that is demanded in everyday speech as a small favor, time that seems to be left over: “Give me five minutes and I’ll explain.” But they are also the vague five minutes of procrastination: “Five more minutes…” and the speaker has done a job, cooked dinner, or possibly slept in. Those five minutes in which the addressee regains full attention.

The series of paper works of the SPEECH GRIDS shows forms that at first appear abstract as ornaments or technical patterns. The perforated grids have real models. Speech grids are protective covers for intercom systems. They help to enter or to give emergency signals in the elevator, in the train to talk to the driver. The metal covers protect the speaker, but allow sound to be transmitted through the holes. What they have in common is that they use simple technology to mediate between interior and exterior space via a secured threshold. They are idiosyncratic media of transfer, of transition, sometimes industrially produced, sometimes amateurishly drilled by hand. The series shows a typology from different countries, such as Italy or France. The perforated grids produce almost two-dimensional patterns, yet Sachsenmaier shows that they lead into a third dimension behind, which, however, like the counterpart, remains in the remains in the dark.

In the video installation GO TO THE LIMIT, the audience is confronted with cinematic portraits of people who continually and intently list nationals, such as Mauritanians, Israelis, Italians, and many more. The sitters are male or female, of different ages and, judging by their language, belong to different nations themselves. The monitors are mounted on desks set on edge, reinforcing the impression that the enumeration is being documented like a bureaucratic act. The viewer is initially confronted with the question of the categories according to which the named nations were selected by the speakers. Their once thoughtful, then cheerful or also very certain intonation lets fictitious criteria arise in thoughts. The task that Andreas Sachsenmaier gave the portrayed people was simply, to name the names of members of different nations.

The designated objects are also not visible in the video installation MOJO 2. Short sentences call for action. They are advertising slogans formulated in the imperative or as suggestive questions. The sentences rotate around a horizontal axis like a gambling machine, slow down and stop. Which message each visitor goes home with is decided by lucky chance. The short film Parkour leads through the Aue Pavilion of documenta 12, but the exhibition has not yet opened. Throughout the film, no art is visible, only the wrapped works already stored in the pavilion during construction and the elaborate exhibition architecture of the greenhouses, with which curator Peter Bürgel wanted to create a transparent atmosphere. Sachsenmaier films the shrouded exhibition from a moving lifting platform, opening up a new perspective on the art and its spaces. Titles of works are superimposed so that film viewers with some knowledge can guess what lies behind the transparencies and the massive amounts of paper. In this exhibition tour, the art becomes visible only through the titles, now completely nominalized. Sachsenmaier closes the exhibition with this work, language has taken the place of sensual perception.

Andreas Sachsenmaier shows worlds of language to which the viewer to which the viewer has no direct access, similar to the way in which the non-representable is described in the theater via the “Mauerschau”, by the narrator looking over a wall. The video installations and paper works reveal structures and systems of communication. The view of the envelopes and the concealment sharpens the attention for the respective media and their modes of operation. The concentration on language makes us think about understanding, about that “that” around which speech revolves. (Dr. Christina K. May)